Basis (linear algebra)

Template:Redirect Template:Redirects here

In mathematics, a set Template:Mvar of elements (vectors) in a vector space Template:Math is called a basis, if every element of Template:Math may be written in a unique way as a (finite) linear combination of elements of Template:Mvar. The coefficients of this linear combination are referred to as components or coordinates on Template:Mvar of the vector. The elements of a basis are called Template:Visible anchor.

Equivalently Template:Mvar is a basis if its elements are linearly independent and every element of Template:Mvar is a linear combination of elements of Template:Mvar.[1] In more general terms, a basis is a linearly independent spanning set.

A vector space can have several bases; however all the bases have the same number of elements, called the dimension of the vector space.

Definition

A basis Template:Math of a vector space Template:Math over a field Template:Math (such as the real numbers Template:Math or the complex numbers Template:Math) is a linearly independent subset of Template:Math that spans Template:Mvar. This means that a subset Template:Mvar of Template:Math is a basis if it satisfies the two following conditions:

- the linear independence property:

- for every finite subset Template:Math of Template:Mvar and every Template:Math in Template:Math, if Template:Math, then necessarily Template:Math;

- the spanning property:

- for every (vector) Template:Math in Template:Math, it is possible to choose Template:Math in Template:Math and Template:Math in Template:Mvar such that Template:Math.

The scalars Template:Math are called the coordinates of the vector Template:Math with respect to the basis Template:Math, and by the first property they are uniquely determined.

A vector space that has a finite basis is called finite-dimensional. In this case, the subset Template:Math that is considered (twice) in the above definition may be chosen as Template:Mvar itself.

It is often convenient or even necessary to have an ordering on the basis vectors, e.g. for discussing orientation, or when one considers the scalar coefficients of a vector with respect to a basis, without referring explicitly to the basis elements. In this case, the ordering is necessary for associating each coefficient to the corresponding basis element. This ordering can be done by numbering the basis elements. For example, when dealing with (m, n)-matrices, the Template:Math element (in the Template:Mvarth row and Template:Mvarth column) can be referred to the Template:Mathth element of a basis consisting of the (m, n)-unit-matrices (varying column-indices before row-indices). For emphasizing that an order has been chosen, one speaks of an ordered basis, which is therefore not simply an unstructured set, but e.g. a sequence, or an indexed family, or similar; see Ordered bases and coordinates below.

Examples

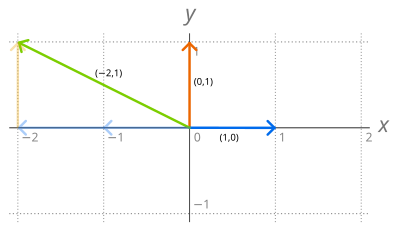

- The set [[exponentiation over sets|Template:Math]] of the ordered pairs of real numbers is a vector space for the component-wise addition

- and scalar multiplication

- where is any real number. A simple basis of this vector space, called the standard basis consists of the two vectors Template:Math and Template:Math, since, any vector Template:Math of Template:Math may be uniquely written as

- Any other pair of linearly independent vectors of Template:Math, such as Template:Math and Template:Math, forms also a basis of R2.

- More generally, if Template:Mvar is a field, the set of [[tuple|Template:Mvar-tuples]] of elements of Template:Mvar is a vector space for similarly defined addition and scalar multiplication. Let

- be the Template:Mvar-tuple with all components equal to 0, except the Template:Mvarth, which is 1. Then is a basis of which is called the standard basis of

- If Template:Mvar is a field, the polynomial ring Template:Math of the polynomials in one indeterminate has a basis Template:Mvar, called the monomial basis, consisting of all monomials:

- Any set of polynomials such that there is exactly one polynomial of each degree is also a basis. Such a set of polynomials is called a polynomial sequence. Example (among many) of such polynomial sequences are Bernstein basis polynomials, and Chebyshev polynomials.

Properties

Many properties of finite bases result from the Steinitz exchange lemma, which states that, given a finite spanning set Template:Mvar and a linearly independent subset Template:Mvar of Template:Mvar elements of Template:Mvar, one may replace Template:Mvar well chosen elements of Template:Mvar by the elements of Template:Mvar for getting a spanning set containing Template:Mvar, having its other elements in Template:Mvar, and having the same number of elements as Template:Mvar.

Most properties resulting from the Steinitz exchange lemma remain true when there is no finite spanning set, but their proof in the infinite case requires generally the axiom of choice or a weaker form of it, such as the ultrafilter lemma.

If Template:Mvar is a vector space over a field Template:Mvar, then:

- If Template:Mvar is a linearly independent subset of a spanning set Template:Math, then there is a basis Template:Mvar such that

- Template:Mvar has a basis (this is the preceding property with Template:Mvar being the empty set, and Template:Math).

- All bases of Template:Mvar have the same cardinality, which is called the dimension of Template:Mvar. This is the dimension theorem.

- A generating set Template:Mvar is a basis of Template:Mvar if and only if it is minimal, that is, no proper subset of Template:Mvar is also a generating set of Template:Mvar.

- A linearly independent set Template:Mvar is a basis if and only if it is maximal, that is, it is not a proper subset of any linearly independent set.

If Template:Mvar is a vector space of dimension Template:Mvar, then:

- A subset of Template:Mvar with Template:Mvar elements is a basis if and only if it is linearly independent.

- A subset of Template:Mvar with Template:Mvar elements is a basis if and only if it is spanning set of Template:Mvar.

Coordinates Template:Anchor

Let Template:Mvar be a vector space of finite dimension Template:Mvar over a field Template:Mvar, and

be a basis of Template:Mvar. By definition of a basis, for every Template:Mvar in Template:Mvar may be written, in a unique way,

where the coefficients are scalars (that is, elements of Template:Mvar), which are called the coordinates of Template:Mvar over Template:Mvar. However, if one talks of the set of the coefficients, one looses the correspondence between coefficients and basis elements, and several vectors may have the same set of coefficients. For example, and have the same set of coefficients Template:Math, and are different. It is therefore often convenient to work with an ordered basis; this is typically done by indexing the basis elements by the first natural numbers. Then, the coordinates of a vector form a sequence similarly indexed, and a vector is completely characterized by the sequence of coordinates. An ordered basis is also called a frame, a word commonly used, in various contexts, for referring to a sequence of data allowing defining coordinates.

Let, as usual, be the set of the [[tuple|Template:Mvar-tuples]] of elements of Template:Mvar. This set is an Template:Mvar-vector space, with addition and scalar multiplication defined component-wise. The map

is a linear isomorphism from the vector space onto Template:Mvar. In other words, is the coordinate space of Template:Mvar, and the Template:Mvar-tuple is the coordinate vector of Template:Mvar.

The inverse image by of is the Template:Mvar-tuple all of whose components are 0, except the Template:Mvarth that is 1. The form an ordered basis of which is called its standard basis or canonical basis. The ordered basis Template:Mvar is the image by of the canonical basis of

It follows from what precedes that every ordered basis is the image by a linear isomorphism of the canonical basis of and that every linear isomorphism from onto Template:Mvar may be defined as the isomorphism that maps the canonical basis of onto a given ordered basis of Template:Mvar. In other words it is equivalent to define an ordered basis of Template:Mvar, or a linear isomorphism from onto Template:Mvar.

Change of basis

Template:Main Let Template:Math be a vector space of dimension Template:Mvar over a field Template:Math. Given two (ordered) bases and of Template:Math, it is often useful to express the coordinates of a vector Template:Mvar with respect to in terms of the coordinates with respect to This can be done by the change-of-basis formula, that is described below. The subscripts "old" and "new" have been chosen because it is customary to refer to and as the old basis and the new basis, respectively. It is useful to describe the old coordinates in terms of the new ones, because, in general, one has expressions involving the old coordinates, and if one wants to obtain equivalent expressions in terms of the new coordinates; this is obtained by replacing the old coordinates by their expressions in terms of the new coordinates.

Typically, the new basis vectors are given by their coordinates over the old basis, that is,

If and are the coordinates of a vector Template:Mvar over the old and the new basis respectively, the change-of-basis formula is

for Template:Math.

This formula may be concisely written in matrix notation. Let Template:Mvar be the matrix of the and

- and

be the column vectors of the coordinates of Template:Mvar in the old and the new basis respectively, then the formula for changing coordinates is

The formula can be proven by considering the decomposition of the vector Template:Mvar on the two bases: one has

and

The change-of-basis formula results then from the uniqueness of the decomposition of a vector over a basis, here that is

for Template:Math.

Related notions

Free module

Template:Main If one replaces the field occurring in the definition of a vector space by a ring, one gets the definition of a module. For modules, linear independence and spanning sets are defined exactly as for vector spaces, although "generating set" is more commonly used than that of "spanning set".

Like for vector spaces, a basis of a module is a linearly independent subset that is also a generating set. A major difference with the theory of vector spaces is that not every module has a basis. A module that has a basis is called a free module. Free modules play a fundamental role in module theory, as they may be used for describing the structure of non-free modules through free resolutions.

A module over the integers is exactly the same thing as an abelian group. Thus a free module over the integers is also a free abelian group. Free abelian groups have specific properties that are not shared by modules over other rings. Specifically, every subgroup of a free abelian group is a free abelian group, and, if Template:Mvar is a subgroup of a finitely generated free abelian group Template:Mvar (that is an abelian group that has a finite basis), there is a basis of Template:Mvar and an integer Template:Math such that is a basis of Template:Mvar, for some nonzero integers For details, see Template:Slink.

Analysis

In the context of infinite-dimensional vector spaces over the real or complex numbers, the term Template:Visible anchor (named after Georg Hamel) or algebraic basis can be used to refer to a basis as defined in this article. This is to make a distinction with other notions of "basis" that exist when infinite-dimensional vector spaces are endowed with extra structure. The most important alternatives are orthogonal bases on Hilbert spaces, Schauder bases, and Markushevich bases on normed linear spaces. In the case of the real numbers R viewed as a vector space over the field Q of rational numbers, Hamel bases are uncountable, and have specifically the cardinality of the continuum, which is the cardinal number where is the smallest infinite cardinal, the cardinal of the integers.

The common feature of the other notions is that they permit the taking of infinite linear combinations of the basis vectors in order to generate the space. This, of course, requires that infinite sums are meaningfully defined on these spaces, as is the case for topological vector spaces – a large class of vector spaces including e.g. Hilbert spaces, Banach spaces, or Fréchet spaces.

The preference of other types of bases for infinite-dimensional spaces is justified by the fact that the Hamel basis becomes "too big" in Banach spaces: If X is an infinite-dimensional normed vector space which is complete (i.e. X is a Banach space), then any Hamel basis of X is necessarily uncountable. This is a consequence of the Baire category theorem. The completeness as well as infinite dimension are crucial assumptions in the previous claim. Indeed, finite-dimensional spaces have by definition finite bases and there are infinite-dimensional (non-complete) normed spaces which have countable Hamel bases. Consider , the space of the sequences of real numbers which have only finitely many non-zero elements, with the norm Its standard basis, consisting of the sequences having only one non-zero element, which is equal to 1, is a countable Hamel basis.

Example

In the study of Fourier series, one learns that the functions {1} ∪ { sin(nx), cos(nx) : n = 1, 2, 3, ... } are an "orthogonal basis" of the (real or complex) vector space of all (real or complex valued) functions on the interval [0, 2π] that are square-integrable on this interval, i.e., functions f satisfying

The functions {1} ∪ { sin(nx), cos(nx) : n = 1, 2, 3, ... } are linearly independent, and every function f that is square-integrable on [0, 2π] is an "infinite linear combination" of them, in the sense that

for suitable (real or complex) coefficients ak, bk. But many[2] square-integrable functions cannot be represented as finite linear combinations of these basis functions, which therefore do not comprise a Hamel basis. Every Hamel basis of this space is much bigger than this merely countably infinite set of functions. Hamel bases of spaces of this kind are typically not useful, whereas orthonormal bases of these spaces are essential in Fourier analysis.

Geometry

The geometric notions of an affine space, projective space, convex set, and cone have related notions of Template:Anchor basis.[3] An affine basis for an n-dimensional affine space is points in general linear position. A Template:Visible anchor is points in general position, in a projective space of dimension n. A Template:Visible anchor of a polytope is the set of the vertices of its convex hull. A Template:Visible anchor[4] consists of one point by edge of a polygonal cone. See also a Hilbert basis (linear programming).

Random basis

For a probability distribution in Rn with a probability density function, such as the equidistribution in a n-dimensional ball with respect to Lebesgue measure, it can be shown that n randomly and independently chosen vectors will form a basis with probability one, which is due to the fact that n linearly dependent vectors x1, ..., xn in Rn should satisfy the equation Template:Nowrap (zero determinant of the matrix with columns xi), and the set of zeros of a non-trivial polynomial has zero measure. This observation has led to techniques for approximating random bases.[5][6]

It is difficult to check numerically the linear dependence or exact orthogonality. Therefore, the notion of ε-orthogonality is used. For spaces with inner product, x is ε-orthogonal to y if (that is, cosine of the angle between x and y is less than ε).

In high dimensions, two independent random vectors are with high probability almost orthogonal, and the number of independent random vectors, which all are with given high probability pairwise almost orthogonal, grows exponentially with dimension. More precisely, consider equidistribution in n-dimensional ball. Choose N independent random vectors from a ball (they are independent and identically distributed). Let θ be a small positive number. Then for

N random vectors are all pairwise ε-orthogonal with probability Template:Nowrap.[6] This N growth exponentially with dimension n and for sufficiently big n. This property of random bases is a manifestation of the so-called measure concentration phenomenon.[7]

The figure (right) illustrates distribution of lengths N of pairwise almost orthogonal chains of vectors that are independently randomly sampled from the n-dimensional cube Template:Nowrap as a function of dimension, n. A point is first randomly selected in the cube. The second point is randomly chosen in the same cube. If the angle between the vectors was within Template:Nowrap then the vector was retained. At the next step a new vector is generated in the same hypercube, and its angles with the previously generated vectors are evaluated. If these angles are within Template:Nowrap then the vector is retained. The process is repeated until the chain of almost orthogonality breaks, and the number of such pairwise almost orthogonal vectors (length of the chain) is recorded. For each n, 20 pairwise almost orthogonal chains where constructed numerically for each dimension. Distribution of the length of these chains is presented.

Proof that every vector space has a basis

Let V be any vector space over some field F. Let X be the set of all linearly independent subsets of V.

The set X is nonempty since the empty set is an independent subset of V, and it is partially ordered by inclusion, which is denoted, as usual, by Template:Math.

Let Y be a subset of X that is totally ordered by Template:Math, and let LY be the union of all the elements of Y (which are themselves certain subsets of V).

Since (Y, ⊆) is totally ordered, every finite subset of LY is a subset of an element of Y, which is a linearly independent subset of V, and hence every finite subset of LY is linearly independent. Thus LY is linearly independent, so LY is an element of X. Therefore, LY is an upper bound for Y in (X, ⊆): it is an element of X, that contains every element Y.

As X is nonempty, and every totally ordered subset of (X, ⊆) has an upper bound in X, Zorn's lemma asserts that X has a maximal element. In other words, there exists some element Lmax of X satisfying the condition that whenever Lmax ⊆ L for some element L of X, then L = Lmax.

It remains to prove that Lmax is a basis of V. Since Lmax belongs to X, we already know that Lmax is a linearly independent subset of V.

If Lmax would not span V, there would exist some vector w of V that cannot be expressed as a linear combination of elements of Lmax (with coefficients in the field F). In particular, w cannot be an element of Lmax. Let Lw = Lmax ∪ {w}. This set is an element of X, that is, it is a linearly independent subset of V (because w is not in the span of Lmax, and Lmax is independent). As Lmax ⊆ Lw, and Lmax ≠ Lw (because Lw contains the vector w that is not contained in Lmax), this contradicts the maximality of Lmax. Thus this shows that Lmax spans V.

Hence Lmax is linearly independent and spans V. It is thus a basis of V, and this proves that every vector space has a basis.

This proof relies on Zorn's lemma, which is equivalent to the axiom of choice. Conversely, it has been proved that if every vector space has a basis, then the axiom of choice is true.[8] Thus the two assertions are equivalent.

See also

Notes

References

General references

Historical references

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation, reprint: Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

External links

- Instructional videos from Khan Academy

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Springer

Template:Linear algebra Template:Tensors

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Note that one cannot say "most" because the cardinalities of the two sets (functions that can and cannot be represented with a finite number of basis functions) are the same.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Blass, Andrea (1984). Existence of bases implies the Axiom of Choice. Contemporary Mathematics. 31. pp. 31-33.