Absolute magnitude

Absolute magnitude (Template:Mvar) is a measure of the luminosity of a celestial object, on an inverse logarithmic astronomical magnitude scale. An object's absolute magnitude is defined to be equal to the apparent magnitude that the object would have if it were viewed from a distance of exactly Template:Convert, without extinction (or dimming) of its light due to absorption by interstellar matter and cosmic dust. By hypothetically placing all objects at a standard reference distance from the observer, their luminosities can be directly compared on a magnitude scale.

As with all astronomical magnitudes, the absolute magnitude can be specified for different wavelength ranges corresponding to specified filter bands or passbands; for stars a commonly quoted absolute magnitude is the absolute visual magnitude, which uses the visual (V) band of the spectrum (in the UBV photometric system). Absolute magnitudes are denoted by a capital M, with a subscript representing the filter band used for measurement, such as MV for absolute magnitude in the V band.

The more luminous an object, the smaller the numerical value of its absolute magnitude. A difference of 5 magnitudes between the absolute magnitudes of two objects corresponds to a ratio of 100 in their luminosities, and a difference of n magnitudes in absolute magnitude corresponds to a luminosity ratio of 100(n/5). For example, a star of absolute magnitude MV=3.0 would be 100 times more luminous than a star of absolute magnitude MV=8.0 as measured in the V filter band. The Sun has absolute magnitude MV=+4.83.[1] Highly luminous objects can have negative absolute magnitudes: for example, the Milky Way galaxy has an absolute B magnitude of about −20.8.[2]

An object's absolute bolometric magnitude (Mbol) represents its total luminosity over all wavelengths, rather than in a single filter band, as expressed on a logarithmic magnitude scale. To convert from an absolute magnitude in a specific filter band to absolute bolometric magnitude, a bolometric correction (BC) is applied.[3]

For Solar System bodies that shine in reflected light, a different definition of absolute magnitude (H) is used, based on a standard reference distance of one astronomical unit.

Stars and galaxies

In stellar and galactic astronomy, the standard distance is 10 parsecs (about 32.616 light-years, 308.57 petameters or 308.57 trillion kilometres). A star at 10 parsecs has a parallax of 0.1″ (100 milliarcseconds). Galaxies (and other extended objects) are much larger than 10 parsecs, their light is radiated over an extended patch of sky, and their overall brightness cannot be directly observed from relatively short distances, but the same convention is used. A galaxy's magnitude is defined by measuring all the light radiated over the entire object, treating that integrated brightness as the brightness of a single point-like or star-like source, and computing the magnitude of that point-like source as it would appear if observed at the standard 10 parsecs distance. Consequently, the absolute magnitude of any object equals the apparent magnitude it would have if it were 10 parsecs away.

The measurement of absolute magnitude is made with an instrument called a bolometer. When using an absolute magnitude, one must specify the type of electromagnetic radiation being measured. When referring to total energy output, the proper term is bolometric magnitude. The bolometric magnitude usually is computed from the visual magnitude plus a bolometric correction, Template:Math. This correction is needed because very hot stars radiate mostly ultraviolet radiation, whereas very cool stars radiate mostly infrared radiation (see Planck's law).

Some stars visible to the naked eye have such a low absolute magnitude that they would appear bright enough to outshine the planets and cast shadows if they were at 10 parsecs from the Earth. Examples include Rigel (−7.0), Deneb (−7.2), Naos (−6.0), and Betelgeuse (−5.6). For comparison, Sirius has an absolute magnitude of 1.4, which is brighter than the Sun, whose absolute visual magnitude is 4.83 (it actually serves as a reference point). The Sun's absolute bolometric magnitude is set arbitrarily, usually at 4.75.[4][5] Absolute magnitudes of stars generally range from −10 to +17. The absolute magnitudes of galaxies can be much lower (brighter). For example, the giant elliptical galaxy M87 has an absolute magnitude of −22 (i.e. as bright as about 60,000 stars of magnitude −10).

Apparent magnitude

The Greek astronomer Hipparchus established a numerical scale to describe the brightness of each star appearing in the sky. The brightest stars in the sky were assigned an apparent magnitude Template:Math, and the dimmest stars visible to the naked eye are assigned Template:Math.[6] The difference between them corresponds to a factor of 100 in brightness. For objects within the immediate neighborhood of the Sun, the absolute magnitude Template:Mvar and apparent magnitude Template:Mvar from any distance Template:Mvar (in parsecs) is related by:

where Template:Mvar is the radiant flux measured at distance Template:Mvar (in parsecs), Template:Math the radiant flux measured at distance Template:Math. The relation can be written in terms of logarithm:

where the insignificance of extinction by gas and dust is assumed. Typical extinction rates within the galaxy are 1 to 2 magnitudes per kiloparsec, when dark clouds are taken into account.[7]

For objects at very large distances (outside the Milky Way) the luminosity distance Template:Math (distance defined using luminosity measurements) must be used instead of Template:Mvar (in parsecs), because the Euclidean approximation is invalid for distant objects and general relativity must be taken into account. Moreover, the cosmological redshift complicates the relation between absolute and apparent magnitude, because the radiation observed was shifted into the red range of the spectrum. To compare the magnitudes of very distant objects with those of local objects, a K correction might have to be applied to the magnitudes of the distant objects.

The absolute magnitude Template:Mvar can also be approximated using apparent magnitude Template:Mvar and stellar parallax Template:Mvar:

or using apparent magnitude Template:Mvar and distance modulus Template:Mvar:

- .

Examples

Rigel has a visual magnitude Template:Math of 0.12 and distance about 860 light-years

Vega has a parallax Template:Mvar of 0.129″, and an apparent magnitude Template:Math of 0.03

The Black Eye Galaxy has a visual magnitude Template:Math of 9.36 and a distance modulus Template:Mvar of 31.06

Bolometric magnitude

The bolometric magnitude Template:Math, takes into account electromagnetic radiation at all wavelengths. It includes those unobserved due to instrumental passband, the Earth's atmospheric absorption, and extinction by interstellar dust. It is defined based on the luminosity of the stars. In the case of stars with few observations, it must be computed assuming an effective temperature.

Classically, the difference in bolometric magnitude is related to the luminosity ratio according to:[6]

which makes by inversion:

where

- Template:Math is the Sun's luminosity (bolometric luminosity)

- Template:Math is the star's luminosity (bolometric luminosity)

- Template:Math is the bolometric magnitude of the Sun

- Template:Math is the bolometric magnitude of the star.

In August 2015, the International Astronomical Union passed Resolution B2[8] defining the zero points of the absolute and apparent bolometric magnitude scales in SI units for power (watts) and irradiance (W/m2), respectively. Although bolometric magnitudes had been used by astronomers for many decades, there had been systematic differences in the absolute magnitude-luminosity scales presented in various astronomical references, and no international standardization. This led to systematic differences in bolometric corrections scales.[9] Combined with incorrect assumed absolute bolometric magnitudes for the Sun could lead to systematic errors in estimated stellar luminosities (and stellar properties calculated which rely on stellar luminosity, such as radii, ages, and so on).

Resolution B2 defines an absolute bolometric magnitude scale where Template:Math corresponds to luminosity Template:MathTemplate:Val, with the zero point luminosity Template:Math set such that the Sun (with nominal luminosity Template:Val) corresponds to absolute bolometric magnitude Template:Math4.74. Placing a radiation source (e.g. star) at the standard distance of 10 parsecs, it follows that the zero point of the apparent bolometric magnitude scale Template:Math corresponds to irradiance Template:MathTemplate:Val. Using the IAU 2015 scale, the nominal total solar irradiance ("solar constant") measured at 1 astronomical unit (Template:Val) corresponds to an apparent bolometric magnitude of the Sun of Template:Math−26.832.[9]

Following Resolution B2, the relation between a star's absolute bolometric magnitude and its luminosity is no longer directly tied to the Sun's (variable) luminosity:

where

- Template:Math is the star's luminosity (bolometric luminosity) in watts

- Template:Math is the zero point luminosity Template:Val

- Template:Math is the bolometric magnitude of the star

The new IAU absolute magnitude scale permanently disconnects the scale from the variable Sun. However, on this SI power scale, the nominal solar luminosity corresponds closely to Template:Math4.74, a value that was commonly adopted by astronomers before the 2015 IAU resolution.[9]

The luminosity of the star in watts can be calculated as a function of its absolute bolometric magnitude Template:Math as:

using the variables as defined previously.

Solar System bodies (Template:Mvar)

| H | Diameter |

|---|---|

| 10 | 34 km |

| 12.6 | 10 km |

| 15 | 3.4 km |

| 17.6 | 1 km |

| 19.2 | 500 meter |

| 20 | 340 meter |

| 22.6 | 100 meter |

| 24.2 | 50 meter |

| 25 | 34 meter |

| 27.6 | 10 meter |

| 30 | 3.4 meter |

For planets and asteroids a definition of absolute magnitude that is more meaningful for non-stellar objects is used. The absolute magnitude, commonly called , is defined as the apparent magnitude that the object would have if it were one Astronomical Unit (AU) from both the Sun and the observer, and in conditions of ideal solar opposition (an arrangement that is impossible in practice).[11] Solar System bodies are illuminated by the Sun, therefore the magnitude varies as a function of illumination conditions, described by the phase angle. This relationship is referred to as the phase curve. The absolute magnitude is the brightness at phase angle zero, an arrangement known as opposition.

Apparent magnitude

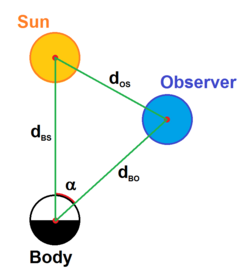

The absolute magnitude can be used to calculate the apparent magnitude of a body. For an object reflecting sunlight, and are connected by the relation

where is the phase angle, the angle between the body-Sun and body–observer lines. is the phase integral (the integration of reflected light; a number in the 0 to 1 range).[12]

By the law of cosines, we have:

Distances:

- Template:Math is the distance between the body and the observer

- Template:Math is the distance between the body and the Sun

- Template:Math is the distance between the observer and the Sun

- Template:Math is 1 AU, the average distance between the Earth and the Sun

Approximations for phase integral

The value of depends on the properties of the reflecting surface, in particular on its roughness. In practice, different approximations are used based on the known or assumed properties of the surface.[12]

Planets

Planetary bodies can be approximated reasonably well as ideal diffuse reflecting spheres. Let be the phase angle in degrees, then[13]

A full-phase diffuse sphere reflects two-thirds as much light as a diffuse flat disk of the same diameter. A quarter phase () has as much light as full phase ().

For contrast, a diffuse disk reflector model is simply , which isn't realistic, but it does represent the opposition surge for rough surfaces that reflect more uniform light back at low phase angles.

The definition of the geometric albedo , a measure for the reflectivity of planetary surfaces, is based on the diffuse disk reflector model. The absolute magnitude , diameter (in kilometers) and geometric albedo of a body are related by[14][15]

- km.

Example: The Moon's absolute magnitude can be calculated from its diameter and geometric albedo :[16]

We have , At quarter phase, (according to the diffuse reflector model), this yields an apparent magnitude of The actual value is somewhat lower than that, The phase curve of the Moon is too complicated for the diffuse reflector model.[17]

More advanced models

Because Solar System bodies are never perfect diffuse reflectors, astronomers use different models to predict apparent magnitudes based on known or assumed properties of the body.[12] For planets, approximations for the correction term in the formula for Template:Mvar have been derived empirically, to match observations at different phase angles. The approximations recommended by the Astronomical Almanac[18] are (with in degrees):

| Planet | Approximation for | |

|---|---|---|

| Mercury | −0.613 | |

| Venus | −4.384 |

|

| Earth | −3.99 | |

| Mars | −1.601 |

|

| Jupiter | −9.395 |

|

| Saturn | −8.914 |

|

| Uranus | −7.110 | (for ) |

| Neptune | −7.00 | (for and ) |

Here is the effective inclination of Saturn's rings (their tilt relative to the observer), which as seen from Earth varies between 0° and 27° over the course of one Saturn orbit, and is a small correction term depending on Uranus' sub-Earth and sub-solar latitudes. is the Common Era year. Neptune's absolute magnitude is changing slowly due to seasonal effects as the planet moves along its 165-year orbit around the Sun, and the approximation above is only valid after the year 2000. For some circumstances, like for Venus, no observations are available, and the phase curve is unknown in those cases.

Example: On 1 January 2019, Venus was from the Sun, and from Earth, at a phase angle of (near quarter phase). Under full-phase conditions, Venus would have been visible at Accounting for the high phase angle, the correction term above yields an actual apparent magnitude of This is close to the value of predicted by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.[19]

Earth's albedo varies by a factor of 6, from 0.12 in the cloud-free case to 0.76 in the case of altostratus cloud. The absolute magnitude here corresponds to an albedo of 0.434. Earth's apparent magnitude cannot be predicted as accurately as that of most other planets.[18]

Asteroids

If an object has an atmosphere, it reflects light more or less isotropically in all directions, and its brightness can be modelled as a diffuse reflector. Atmosphereless bodies, like asteroids or moons, tend to reflect light more strongly to the direction of the incident light, and their brightness increases rapidly as the phase angle approaches . This rapid brightening near opposition is called the opposition effect. Its strength depends on the physical properties of the body's surface, and hence it differs from asteroid to asteroid.[12]

In 1985, the IAU adopted the semi-empirical -system, based on two parameters and called absolute magnitude and slope, to model the opposition effect for the ephemerides published by the Minor Planet Center.[20]

where

- the phase integral is

and

- for or , , , and .[21]

This relation is valid for phase angles , and works best when .[22]

The slope parameter relates to the surge in brightness, typically Template:Val, when the object is near opposition. It is known accurately only for a small number of asteroids, hence for most asteroids a value of is assumed.[22] In rare cases, can be negative.[21][23] An example is 101955 Bennu, with .[24]

In 2012, the -system was officially replaced by an improved system with three parameters , and , which produces more satisfactory results if the opposition effect is very small or restricted to very small phase angles. However, as of 2019, this -system has not been adopted by either the Minor Planet Center nor Jet Propulsion Laboratory.[12][25]

The apparent magnitude of asteroids varies as they rotate, on time scales of seconds to weeks depending on their rotation period, by up to or more.[26] In addition, their absolute magnitude can vary with the viewing direction, depending on their axial tilt. In many cases, neither the rotation period nor the axial tilt are known, limiting the predictability. The models presented here do not capture those effects.[22][12]

Cometary magnitudes

The brightness of comets is given separately as total magnitude (, the brightness integrated over the entire visible extend of the coma) and nuclear magnitude (, the brightness of the core region alone).[27] Both are different scales than the magnitude scale used for planets and asteroids, and can not be used for a size comparison with an asteroid's absolute magnitude Template:Mvar.

The activity of comets varies with their distance from the Sun. Their brightness can be approximated as

where are the total and nuclear apparent magnitudes of the comet, respectively, are its "absolute" total and nuclear magnitudes, and are the body-sun and body-observer distances, is the Astronomical Unit, and are the slope parameters characterising the comet's activity. For , this reduces to the formula for a purely reflecting body.[28]

For example, the lightcurve of comet C/2011 L4 (PANSTARRS) can be approximated by [29] On the day of its perihelion passage, 10 March 2013, comet PANSTARRS was from the Sun and from Earth. The total apparent magnitude is predicted to have been at that time. The Minor Planet Center gives a value close to that, .[30]

| Comet | Absolute magnitude [31] |

Nucleus diameter |

|---|---|---|

| Comet Sarabat | −3.0 | ≈100 km? |

| Comet Hale-Bopp | −1.3 | 60 ± 20 km |

| Comet Halley | 4.0 | 14.9 x 8.2 km |

| average new comet | 6.5 | ≈2 km[32] |

| 289P/Blanpain (during 1819 outburst) | 8.5[33] | 320 m[34] |

| 289P/Blanpain (normal activity) | 22.9[35] | 320 m |

At the same distance, Comet Hale-Bopp is about 130 times brighter than Comet Halley.[31]

The absolute magnitude of any given comet can vary dramatically. It can change as the comet becomes more or less active over time, or if it undergoes an outburst. This makes it difficult to use the absolute magnitude for a size estimate. When comet 289P/Blanpain was discovered in 1819, its absolute magnitude was estimated as .[33] It was subsequently lost, and was only rediscovered in 2003. At that time, its absolute magnitude had decreased to ,[35] and it was realised that the 1819 apparition coincided with an outburst. 289P/Blanpain reached naked eye brightness (5–8 mag) in 1819, even though it is the comet with the smallest nucleus that has ever been physically characterised, and usually doesn't become brighter than 18 mag.[33][34]

For some comets that have been observed at heliocentric distances large enough to distinguish between light reflected from the coma, and light from the nucleus itself, an absolute magnitude analogous to that used for asteroids has been calculated, allowing to estimate the sizes of their nuclei.[36]

Meteors

For a meteor, the standard distance for measurement of magnitudes is at an altitude of Template:Convert at the observer's zenith.[37][38]

See also

- Hertzsprung–Russell diagram – relates absolute magnitude or luminosity versus spectral color or surface temperature.

- Jansky radio astronomer's preferred unit – linear in power/unit area

- List of most luminous stars

- Photographic magnitude

- Surface brightness – the magnitude for extended objects

- Zero point (photometry) – the typical calibration point for star flux

References

External links

- Reference zero-magnitude fluxes

- International Astronomical Union

- Absolute Magnitude of a Star calculator

- The Magnitude system

- About stellar magnitudes

- Obtain the magnitude of any star – SIMBAD

- Converting magnitude of minor planets to diameter

- Another table for converting asteroid magnitude to estimated diameter

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedSunAbs - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedKarachentsev - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedFlower1996 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedStrobel - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCasagrande - ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCarroll - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedUnsoeld2013 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedIAU_XXIX - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedIAU2015B2 - ↑ CNEOS Asteroid Size Estimator

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLuciuk - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedKarttunen2016 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWhitmell1907 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedsizemagnitude - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMag_formula - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedAlbedo - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLuciuk2 - ↑ 18.0 18.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMallama_and_Hilton - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJPLHorizonsVenus - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMPC1985 - ↑ 21.0 21.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLagerkvist - ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs nameddymock - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJPLdoc - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBennu - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedShevchenko2016 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedlc - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMPES - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMeisel1976 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCOBS 2011L4 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMPC2011L4 - ↑ 31.0 31.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedkidger - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHughes - ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedYoshida - ↑ 34.0 34.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJewitt - ↑ 35.0 35.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJPL_289 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLamy2004 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedIMO - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedSSD_Glossary